We need to talk. PERIOD.

‘That Time of the Month’. ‘Aunt Flo’. ‘The Curse’. ‘Period’. How many different words or phrases can be created to disguise what it is actually called? The Menstrual Cycle.

Menstruation is a health reality for roughly 50 percent of the world’s population, yet conversations about the menstrual cycle have been deemed unacceptable. This is a consequence of not only cultural discomfort but the societal etiquette women have been expected to follow for centuries. Instead of educating young girls on the beauty of their reproductive system and the life it can hold and nourish, they are taught how to manage it privately and discreetly. Behind every culture, there is a long and troubling history of menstrual taboos, which continue to manifest themselves today.

Jane Ussher, professor of Women’s Health Psychology at Western Sydney University, explained, “Periods [have long] been associated with dirt, disgust, and shame, and some might say fear.” She describes this manipulation as misogyny, “a sign of positioning something that is essentially feminine as other, dirty and disgusting.” This stigma that surrounds menstruation has lead to a troubling history of suppression, isolation, and sexism which can be found in countries all over the world today.

Nepal

While the physical ostracization of women on their periods is no longer legal in countries like the United States, the ancient Hindu practice of chhaupadi remains in place in Nepal, parts of India, and Bangladesh. This belief, that is rooted in the belief that menstrual blood is impure, “is a form of seclusion connected to Hindus’ deep religious beliefs and feelings about ritual purity and impurity” explained Mary Cameron, a professor of anthropology at Florida Atlantic University who worked extensively in Nepal. The chhaupadi practice, which is characterized by the banishment of women during menstruation from their usual residence due to the belief of impurity, has long been

criticized for the violation of basic human rights of women and also for the physical and mental health impacts it is associated with. During the isolation process, women are expelled from their homes and forced to stay in small closet-like huts for the duration of their period as well as prohibited from entering the kitchen and touching food, religious icons, cattle, and men.

Though chhauapdi was banned by Nepal’s Supreme Court in 2005, identifying it as a violation of human rights, it has continued to flourish across the country of Nepal, where fear for the consequences of breaking menstrual taboos had taken control. Following the highly publicized deaths of three women in just ten months, who were forced into the inhumane practice of chhauapdi, Nepal’s government took action. The deaths emphasized the dangers of the practice, which put women at risk of violence, rape, a plethora of health issues, and death. In August 2017, Nepal’s Parliament criminalized chhaupadi, passing a law that reads: “A woman during her menstruation or post-natal state should not be kept in chhaupadi or treated with any kind of similar discrimination or untouchable and inhuman behaviour”. Though women’s rights activists indicate this is a step in the right direction, they were quick to point out that one law is not powerful enough to rid the country of the deep-rooted practice that is written in Hindu scriptures. A deeper cultural transformation is required.

China

According to the Guardian, only 2% of women in China use tampons. This is reportedly due to the belief that using a tampon will tear the hymen and rob them of their virginity. The hymen, a membrane that stretches across the vaginal orifice is insignificant in the purpose of the female reproductive system. Dr. Jonathan Schaffir, an ob-gyn at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, reveals this misunderstood tissue to be remnants of the development of the vagina during embryonic growth. What societies across the world have glorified as the sole representation of a woman’s sexual purity is nothing of the sort, just some leftover tissue. This realization accompanied by the cultivation that the hymen is quite easily torn through exercise, tampons, medical exams, and just over time reveals how critical society has trained us to be when discussing the woman’s reproductive system.

Among Chinese women, there is an extreme lack of education surrounding sex and their body parts, which exerts the country’s “virginity fetish”. Those with this fetish consider a girl’s virginity to be the one trait that defines her character. Hymenoplasties, nicknamed ‘revirginity’ is an extremely common surgical procedure in China, designed to repair and reconstruct the thin, ring-like membrane known as the hymen. The aim of this procedure is to cause bleeding during post-nuptial intercourse, something women feel they need to endure after lying to their fiancés about their sex lives, according to the Shanghaiist. There is a long history behind the emphasis of virginity on Chinese women that continues to exist today as a result of men’s correlation between virginity and love, responsibility, and virtue.

China’s media regulator has also banned feminine hygiene product advertisements on TV during prime time, deeming them “disgusting”. This provokes fear and shame in women, making them think their natural cycle is unacceptable.

Kenya

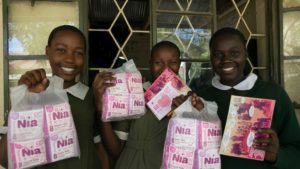

In Kenya, the educational disadvantage young girls and women are put at, is extremely alarming. According to the ZanaAfrica Foundation, 1 in 4 girls do not know they can get pregnant once starting their periods, as well as 95% of girls not knowing that rape, incest, and coercion are violations of their human rights. More than one million girls miss up to six weeks of school each year because they do not have access to the menstrual products that are needed. ZanaAfrica has worked tirelessly to change this, by distributing free menstrual pads to schools in low-income communities and providing health education to increase the number of girls that stay in school. While menstrual taboo still is prevalent in Kenya, National Public Radio notes the political efforts in Kenya have succeeded in increasing access to menstrual products.

India

This year at a hostel in Gujarat’s Bhuj, 70 female college students were pressured by their principal to remove their undergarments to prove that they were not menstruating. This came as a result of the hostel official complaining to the principal that some of them had broken the norms that were enforced while they are on their period. In India, women are not allowed to go to temple, enter the kitchen, or touch other students when they are on their  periods, rules that arestill in place today. At mealtimes, menstruating students are expected to sit away from others, clean their own dishes, and sit on the last bench. The next day, the students alleged that they were abused by the principal and hostel official before they were forced to strip. Three years ago, in a very similar ‘menstruation check’ case, 70 girls aged about 10 years old were forced to strip naked at Kasturba Gandhi Girls Residential School after a female warden found blood on a bathroom door. Discrimination against women on account of menstruation is extremely common and widespread in India, where periods have long been a taboo. In 2017, CNN exposed India for the 12% tax on pads, leaving only 12% of women able to afford this necessity. In recent years, it has become increasingly common for urban educated women to challenge these regressive ideas, and fight for periods to be seen as what they are – a natural biological cycle. Following months of protests and campaigning by activists, India announced it has scrapped its 12% tax on all sanitary products in 2018, a year after the government introduced the tax.

periods, rules that arestill in place today. At mealtimes, menstruating students are expected to sit away from others, clean their own dishes, and sit on the last bench. The next day, the students alleged that they were abused by the principal and hostel official before they were forced to strip. Three years ago, in a very similar ‘menstruation check’ case, 70 girls aged about 10 years old were forced to strip naked at Kasturba Gandhi Girls Residential School after a female warden found blood on a bathroom door. Discrimination against women on account of menstruation is extremely common and widespread in India, where periods have long been a taboo. In 2017, CNN exposed India for the 12% tax on pads, leaving only 12% of women able to afford this necessity. In recent years, it has become increasingly common for urban educated women to challenge these regressive ideas, and fight for periods to be seen as what they are – a natural biological cycle. Following months of protests and campaigning by activists, India announced it has scrapped its 12% tax on all sanitary products in 2018, a year after the government introduced the tax.

The United Kingdom

Statistics published in the Huffington Post reveal that in the UK, over 90% of girls worry about going to school during the duration of their periods because of shame, teasing, fear of leaking, boys knowing, or not being able to go to the bathroom during class. Polling company YouGov found 43% of girls have experienced teasing or jokes about periods by boys – with 40% of this teasing occurring during class time, while teachers are present. The ‘Fear Going to School Less’ report conducted by the menstrual care brand, Bodyform, brought attention to the increase of stigma that has resulted from a failure of period education for boys. The statistics support this statement, with 94% of boys admitting to a clear lack of knowledge about periods, 42% finding the topic to be awkward, and 38% embarrassing. Bodyform has pledged to work with high schools to create positive and informative conversations surrounding periods to normalize and remove the stigma. As a result of the #FreePeriod Campaign by Amika George, the UK government announced in 2019 they are taking measures to ensure sanitary products are free across all schools in England.

The United States

You don’t have to look very hard to identify period stigma in the United States, as it is made evident in many places. Close to 14 million women across the U.S. aged between 12 to 52 live below the poverty line, and most of them don’t have access to sanitary pads. In states like Texas and Alabama, you can buy a Snickers bar from a vending machine tax-free, but when it comes to purchasing a tampon or pad, which are not considered “necessities of life”, women must pay taxes. Due to this tax, women are estimated to spend an additional $150 million per year on menstrual products in the United States. A number of countries around the world have already begun eliminating taxes on menstrual products, but America remains absent from this list. Though some states have been successful in adding pads and tampons to the list of necessary items, 70% of states across the country continue this sales tax.

Period stigma is not only present in convenience stores. In 2015, then presidential candidate Donald Trump, said in an interview with Megyn Kelly that, “you could see there was blood coming out of her eyes. Blood coming out of her wherever.” These denunciations made by sexist men hiding behind society’s cloak of masculinity subdue and mock the pure and essential anatomy of a woman.

The Impact

Feminism has been on the rise in the last decade, but few find it comfortable to engage in conversations about menstruation. In order for women to be looked at and treated equally, there needs to be an acceptance of the period. Rather than dubbed ‘shameful’, ‘impure’, and ‘dirty’, we must acknowledge as a society that it is a natural biological cycle that creates life. Approximately 26% of the world’s population is made up of women of reproductive age, many of which do not have access to basic hygiene or necessary feminine hygiene products. Period poverty coupled with the stigmatization and shame associated with periods, not only restricts the vital knowledge and relationship between a woman and her anatomy but impacts us all on a global scale.

As a global community, to ensure a healthy and prosperous future for girls and women everywhere, we have a responsibility to continue the conversation in order to minimize the stigma that surrounds menstruation.

Join the movement! Fight to end period poverty with these nonprofits.